By Rhitama Basak

“Tensions in the world’s largest democracy. India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi has been dogged by accusations over his attitude to the nation’s Muslim minority. What’s the truth?”

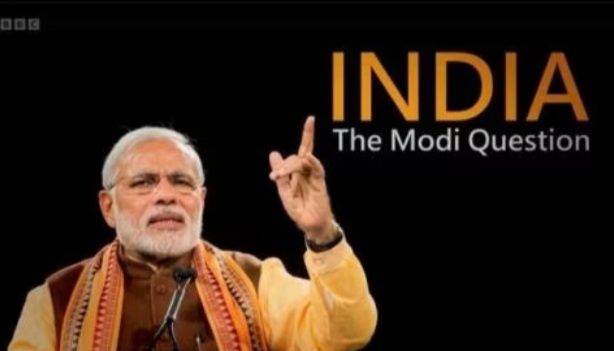

The opening lines appearing on the BBC websites act as a prelude to the now-suppressed documentary, India: The Modi Question. The documentary has been the centre of discussion in India and beyond since its release by BBC Two on January 17, 2023. Made in two parts, the documentary traces Narendra Modi’s rise to power and his association with the right-wing Hindu-supremacist organisations. Drawing global attention to India’s past and present under the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), the documentary has clearly made the BJP-led government anxious, leading to State-imposed ban on the film. In spite of severe repression, screenings of the BBC documentary have been held in university spaces – in Delhi, Kolkata, Mumbai, Hyderabad, parts of Kerala, Rajasthan and other states. Indian students wanting to screen the film have faced backlash – suspension, harassment, detention.

While several incidents of crackdown are reported as the aftermath of the BBC documentary screening across Indian universities, not much is discussed on what makes it so controversial. One of the major reasons for the silence is the unavailability of the documentary film titled India: The Modi Question. By now it is clear that the documentary revisits the 2002 Gujarat pogrom. Since the film has been taken down from the internet, it is imperative to ask what makes the BJP-led State so anxious about a documentary film? Indians who have had the opportunity to watch the film before it was taken down, would know that the perspectives presented are neither new nor exceptional.

However, the film, as it seems, is addressing the collective memory of the masses through both its presence and absence – memory of what the CPIM-AIDWA report had called a “state-sponsored carnage” (2002). The question of the BJP’s (the ruling party in India) complicity in the 2002 targeted massacre of Muslim citizens is only rekindled in the documentary. The incorporation of a previously classified UK-based investigative report in the documentary makes specific claims regarding Narendra Modi’s role in the riots. Meenakshi Ganguly writes for the HRW: “The UK report found Modi was “directly responsible” for the “climate of impunity” that enabled the violence. Many foreign governments, including the UK, stopped engaging with Modi at that time, while the United States revoked his visa” (HRW, January 23, 2023).

A web of narratives has been spun since the post-Godhra period that continue to appeal to the Indian imagination. One of the major narratives being peddled by the Hindutva forces was of the ‘Hindu victimhood’ – one that can neither be justified by the data on 2002 victims or by the state of affairs in contemporary India. As per the official reports, over a thousand were killed, three-fourth of the victims were Muslims. A more recent statement by The Human Rights Watch (HRW) notes, “Wounds heal and human rights obligations are met when there is a true commitment to justice and reform. Instead, BJP supporters have honoured men convicted of gang rape and murder in the 2002 riots” (January 23, 2023).

An air of despair has tormented the survivors for over 20 years now. What is indeed remarkable in the BBC documentary is the lived experiences of the survivors. The first-person accounts of the survivors of Hindutva terror in 2002 Gujarat claim an undeniable credibility – after all a testimony cannot be completely brushed off! The first part of the documentary opens with the testimony of a survivor, a Muslim citizen from Gujarat (who later moved to the US), seeking justice for the members of his family killed in 2002. The film incorporates testimonies on the gruesome assassination of Ehsan Jaffri, testifying to his calm resilience at the face of aggression. In a way, the victimization is not mere numbers when it is viewed on screen through testimonial accounts.

However, the viewer would find the testimonies being constantly interrupted by a member of the BJP whose remarks dilutes the otherwise-vivid ‘narrative vs experience’ dichotomy. It can be asked whether the member of the ruling party in question can comment against the testimonial accounts; but the inclusion of BJP-manufactured narratives in the film debunks the claims of it being ‘biased’, if anything. Given the present-day situation, it is essential to remember that a documentary film does not convict any individual or collective. A ban on the documentary containing lived experiences of the survivors is telling of the extent of State’s intervention in democratic rights of the citizens.

The documentary film not only refers to 2002 Gujarat, but also shows the more recent incidents like the “No-NRC” movement. The viewer will find first-person accounts of the victims of police brutality in 2020 Delhi. From footages of State-sponsored assault on students in Jamia to the ABVP attacking JNU-students, from the targeted violence on Muslims in 2020 Delhi riots to the arrest of activists protesting the discriminatory policies – the film refers to the incidents through testimonies. The film reminds of Faizan (23), beaten to death by men in uniform in the country’s capital in 2020, as his mother shares her trauma on camera. The footage of young Muslim men being beaten and forced to sing the national anthem addresses the fresh wounds on the world’s largest democracy. To hear a survivor of that incident speak makes an immensely powerful impact.

The documentary links Modi’s popularity to the activities of the Sangh (RSS), an organisation that, as described in the film by their own mouthpiece, believes in the “Hindu Rashtra” – a claim that evidently clashes with the idea of a sovereign, secular, democratic, socialist republic. What would such jingoistic fantasies mean for the million Indian Muslims? Can the trajectory of anti-Muslim violence in India be understood in the context of BJP-RSS’ rise to power? The documentary, though banned from the Indian digital space, is to become an international embarrassment for the BJP. Is the State gauging the impact it could have on the students of India to see their peers being violated by Hindutva forces? Will the documentary raise newer and stronger questions on the BJP-RSS-VHP nexus as flag-bearers of militant Hindutva? Will the lived experiences of survivors, when shared at a global forum, counter the State-sponsored narratives of our collective histories? The BJP likes it or not, the questions have been raised.

***

Rhitama is a junior research scholar at the MILLS, Delhi University. She has specialized in South Asian Sufi Reception and Resistance Studies.

Why there is no comment on Godhra from any news quarters. Godhra is an important factor in Gujrat pogram no one is covering it. What happened in Godhra is the key to understand and explain Gujrat pogram.